The Norwegian word lyst is quite frequent in everyday usage, particularly in the common expression Jeg har lyst til å ha X, which is used in the same way English would say ‘I’d like X’, for a request. “Well that sounds just like ‘lust’ to me,” I say to myself. And even though it would be weird in English to say ‘I have a lust to have X’ when asking for a small black coffee the sound and meaning was close enough that I stopped struggling to remember the meaning of lyst from that point on.

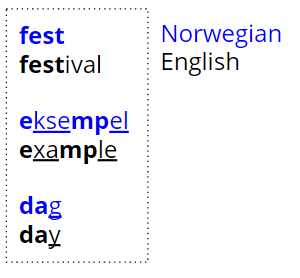

After identifying what I perceived to be a cognate (same origin in an early form of the languages) or a loan (borrowed from one language to another) I would point out the relation to a native speaker of Norwegian to see if they agreed. Often they would not; they didn’t know the English word or felt the sound and or meaning were too different. In the case of lyst I was correct – according to Norwegian lexicographers the origin is low German, with English retaining the original spelling. Emboldened by these early successes, I have accumulated quite a collection in my head of obtuse connections, some more defensible than others. By obtuse, I think I probably actually mean not of Greek or Latin origin – these tend to stand out – like pedagogikk ‘pedagogy’.

| leir /leːʁ/ | sår /soɑʁ/ | sky /ʃi:/ | hund /hʊnd/ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘camp’ | ‘wound’ | ‘cloud’ | ‘dog’ |

| one could camp out in a lair | wounds are often sore | the sky is the cloud place | hound is another word for dog |

(I'm not very confident about my IPA transcriptions here, for the record)

Unfortunately, more recently I have been noticing that this kind of etymological awareness has maybe been affecting my ability to make judgments about my own native English. This came up recently while listening to the most recent edition of my favorite podcast, Lingthusiasm, titled “40: Making machines learn language - Interview with Janelle Shane” in which they discussed strange machine-learning-generated names for ice-cream flavors. One category they called “nuts with mattery”, with examples such as “brown crunch” and “cookies and green”. Mattery is a pretty low frequency English word (I had to look it up) that means ‘producing or containing pus or material resembling pus’.

Gross.

My Norwegian-influenced English word retrieval process assumed “mattery” must mean ‘having to do with food’, because mat is a very common word in Norwegian that literally means ‘food’. The result was that I completely missed the next few lines of dialogue in the podcast and had to listen several times to finally follow the rest of the conversation about these strange ice-cream flavors because “nuts and mattery” meant “nuts and other random foods together” to me.

It may seem like this misunderstanding is somewhat of a limited example that arose because I, for some reason, hadn’t heard the word ‘mattery’ before. In fact, that’s not at all how we remember words. We activate all the meanings for words that sound like the word we are hearing when we are actively listening to and trying to comprehend someone else’s speech, and we (usually) seamlessly and often unconsciously filter out the meanings that don’t make sense. When we encounter a word we haven’t heard before, recently, or don’t know, our mind still tries to process it the way it would words we do know well – by attempting to match the sound to a stored entry. Because languages are all stored together, and because I have a bunch of Norwegian words up in my head these days, I was fooled into thinking an English word was related to a Norwegian one when it wasn’t really – or related far less strongly than my mind wanted it to be.

This also means that I sometimes perceive shared etymologies and relations between Norwegian and English words that are, as far as I can tell, complete fabrications. In Norwegian, bråk means ‘noise’. I remember this because it sounds related to the English 'bracus' – meaning a loud and grating laugh. You know, like ‘raucous’ but specifically for laughing?

Only problem with that is that I made it up.

Bracus is not a word. It’s some sort of idiolectal (specific to me) combination of ‘raucous’ and ‘boisterous’ and ‘roaring’ and ‘blustering’ and, apparently, now also bråk, and who knows what else. But because I now have the word bråk in my mental dictionary I have somehow lost my ability to make a native speaker judgement about the acceptability of “bracus” being a word.

This sort of phenomena is often called “language attrition”. Only I didn’t think it could happen to my native language. I’ve also noticed an uptick of typos in my English writing (which has always been embarrassingly high to begin with) – I’ll have to think about what exactly is going on there some other time. At this rate, soon I’m just going to be grunting and expecting you all to understand what I mean. Kind of like Geralt of Rivia in the Witcher Netflix series.

So is "bracus" a word? No.

Things mentioned in this post:

McCulloch, Gretchen and Gawne, Lauren (hosts). (2020). Making machines learn language - Interview with Janelle Shane [Podcast]. Retrieved from https://lingthusiasm.com/post/190298658151/lingthusiasm-episode-40-making-machines-learn